In the last articles of our series "KPIs for Product Managers" we already described the strategic importance of KPIs Key Performance Indicators KPIs and the basics of Defining KPIs .

In this article, KPI Examples and Explanations some corporate and financial key figures are presented that are or could be important for product management. In no way does this or the following articles claim to be complete, nor does it intend to present a business theory of accounting methods. The focus is on the company and financial key figures that are relevant for product profitability. Some, which experienced readers might miss, can be found in the coming articles sales figures, market figures, marketing figures or product figures. The categorization of KPIs is very different in many companies, so the chosen categories should be seen as a guide.

One of the most important KPI Examples - Revenue

Revenue is likely the most important key figure recorded in any company. Therefore, it can also be seen as a financial and company key figure, although it is also a sales key figure.

Revenue represents the income from the core business. While there are other revenues (e.g. from interest income), in the following we will refer exclusively to the revenues that result from the core business, i.e. the sale of services, products, service or maintenance contracts.

The revenue as the total size of a company is usually divided into different main areas. If there is an exact product allocation, this should be used as a relevant indicator for product management. At the same time, a product manager should always keep in mind what percentage of the total area, product lines or company turnover his products contribute.

Does the product contribute 80% of the company turnover or only 1%? The higher this figure is, the more attention the product and the product manager will receive in the company. Except for new strategic products that open new markets for the company. At the same time, the deviation from the sales plan is the most important comparison that needs to be monitored regularly. If a product contributes 80% of the company's sales, a 10% deviation can have fatal consequences for the annual result, while the same target deviation for a product that contributes only 1% of sales is of course not nice, but less dramatic for the company's result. In order to classify the sales financially correctly, a distinction must be made between the billing revenue and the reconized revenue. This difference is best explained using the following KPI examples:

- Typical Cloud subscription models

- With subscription models for cloud software (formerly also known as Software as a Service, or SaaS for short), annual contracts are usually concluded, which are extended if necessary. Depending on the cost of the solution, the amounts for the first year are usually payable in full in advance. The manufacturer invoices the customer for the entire sum, 12 months times monthly costs of the software (billing revenue). Since the service is to be provided to the customer in 12 equal monthly units in the future, 1/12 of the revenue per month is booked in the balance sheet (recognized revenue). This means 1/12 in the first month and 1/12 in the following months (deferred revenue).

- Income from maintenance

- Similarly, revenue for maintenance or software maintenance must be accounted for accordingly in financial terms, as the customer still receives services in the months following the conclusion of the contract, which it usually pays for in advance.

- Software licenses that are sold

- Conversely, if a software license is purchased that grants the customer the right to use the software for an unlimited period of time (excluding support and maintenance), the full amount is immediately credited in accounting terms to the income in the month in which the order is placed or the invoice is issued or delivered. A typical example is the purchase of Microsoft Office licenses, e.g. Microsoft Office 2010 Professional Edition.

Sales units are often measured by the total revenue generated, i.e. the billing revenue, with a corresponding ratio (target revenue for a sales representative) for new business and business with existing customers or with a breakdown of revenue by product or service revenue. Service revenues in subsequent years are sometimes only credited proportionally to the quota.

If in subscription models the sales are invoiced to the customer on a monthly or quarterly basis, these sales should also be measured precisely.

The revenue forecast, i.e. the estimation of sales for the future, must take corresponding new customer contracts into account. Promotions or campaigns must be calculated correctly. For example, models that are common in the telecommunications industry, "The first 3 months 0 EUR, afterwards only 19.99 EUR" must be taken into account. In this example, billable sales are only calculated after a time delay of 3 months, i.e. from the fourth month.

At least three KPIs are measured for revenue: The target turnover (the annual, quarterly or monthly target, referred to as sales-quote), the forecast, i.e. the estimate of what result will be achieved at the end of the year, quarter or month, and the actual turnover, i.e. how much turnover has already been booked.

If the target turnover is not achieved, the company must analyze and act accordingly. Was the sales figure realistically achievable with the existing sales team or the corresponding channels?

Were there sales shifts between certain sales channels or in certain core industries and target segments?

How much does the forecast deviate from the plan and can this gap be closed?

Are gaps accumulated over the months still closeable or does the annual forecast have to be reduced?

The presentation of the achievement of objectives in percent is an important indicator, but should never be considered alone.

KPI example:

Product 1 runs poorly and ends up at 70% of the target, which is 100.000 EUR, i.e. 70.000 EUR. Product 2 is expected to generate 2 million EUR in the same period and currently only achieves 90% of the target, i.e. 1.8 million EUR.

The missing 10% or 200.000 EUR for product 2 should therefore have the higher focus than the missing 30% or 30.000 of product 1. Although it must be considered in which phase the product is in each case.

If product 1 is in the launch phase, e.g. the second month, and corresponding 24-month-business plans are based on the growth phase from the beginning, then the missing sales are usually potentiated (sum of the missing sales for months 3-24). In this case, therefore, even a 30.000 EUR gap must be remedied and compensated for with the appropriate priority.

Further issues to be considered for sales ratios:

- Do different currencies play a significant role in overall sales and does the company "lose or gain" from currency fluctuations?

- Are there regional differences?

- Are there differences in distribution channels?

- Are there differences in customer segments, or has the company's internal customer segmentation been changed?

Sales managers in particular need to look at these KPIs in even greater detail and derive measures from them. Insofar as a company has different sales managers for e.g. midmarket (SMB), enterprise and/or global accounts, customers are often resegmented at the beginning of a new fiscal year. This sometimes leads to a significant impact on the sales of an individual area or sales channel and makes direct comparison with the previous year difficult.

For example, if a customer that generated EUR 5 million in revenue (license and maintenance) from the Enterprise unit for years is managed by the Global Account team in the next fiscal year, the revenue from one channel automatically shifts to the other channel.

Depending on the percentage of this one customer, it will be a challenge for the enterprise sales team to compensate accordingly for this "loss" and - which will be the rule rather than the exception - to achieve an increase in the previous year's revenue.

Such changes in segmentation, as well as the elimination or addition of products or service components to the sales target, must always be taken into account as soon as comparisons are formed.

Typical comparison periods and quotients that are formed are:

- Quarterly total of sales

- Year comparison (YoY: Year over Year), i.e. the increase in sales in the current quarter for comparison with the prior-year quarterly sales. (YoY increase in percent = (sales Q1/2014 - sales Q1/2013)/sales Q1/2013). Where applicable, the YoY figure is also based on months instead of quarters.

- MoM (Month over Month): the comparison on a monthly basis. (previous month to current month)

- MtD (Month to Date): The actual sales of the current month up to "today".

- QtD (Quarter to Date): The actual sales of the current quarter up to "today".

- YtD (Year to Date): The actual sales of the current fiscal year up to "today".

The Delta planned/actual is measured not only in absolute values but also as a percentage. The forecast/actual or forecast/plan delta is also usually measured.

Whole books could be written about key sales figures and what needs to be taken into account when making comparisons. Essential for this KPI is the understanding of the dependencies, the influencing factors as well as the effects on the respective company strategy. Depending on which phase the company or the respective product is in, different strategies and KPIs make sense.

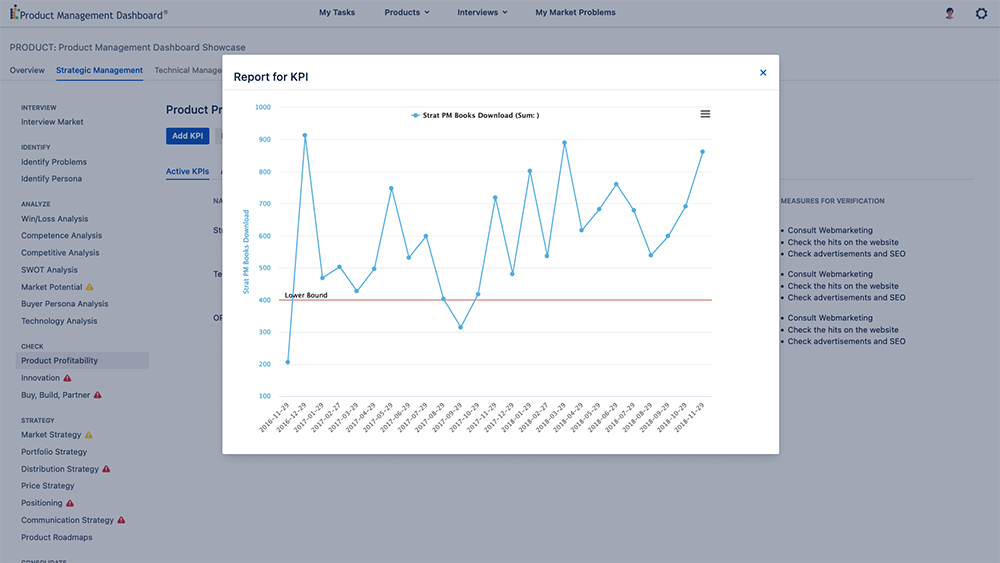

KPI examples - measurement with help of software

All KPIs for the product in one central location and an overview of the product with the aid of Product Management Software

Product Management Dashboard® for JIRA. The KPIs can be measured and entered by various colleagues and departments with upper and lower limits at freely chosen intervals.

An evaluation of the KPIs is carried out automatically. The measures to be taken for exceeding or going below the limits are stored with the parameter

KPI example for rating a company - Gross profit

After revenue, gross profit is usually the first additional KPI for rating a company. Based on net sales, gross profit is calculated from the difference between sales and the Cost of Goods Sold (COGS), which was necessary to achieve the respective sales (e.g., the number of items produced and sold).

Gross Profit = Revenue – Cogs = Cost of goods sold

Sales are based on the net sales of the company, i.e. sales excluding sales tax or value added tax, customer discounts, sales reduced by returns or cancellations.

Gross profit is the ratio of gross profit to sales, i.e. gross margin as a percentage = gross profit/sales * 100% = (sales - cost of goods sold)/sales * 100%.

Gross profit can be calculated per unit, per product, per portfolio, per division or the entire company.

In Germany, a detailed form of contribution margin accounting is common, starting with contribution margin 1 (CM 1) up to contribution margin 4. The designation CM is used when referring to the total quantity.

In the above example, the CM1 in such systems would correspond to the gross profit.

When determining CM2, product fixed costs are also deducted, i.e. fixed costs (e.g. personnel costs) that have to be allocated to the product. In CM3, departmental or group fixed costs are apportioned accordingly, and depending on the granularity, company fixed costs are apportioned in the last section, which finally lead to the overall company profit, the operating profit.

Since companies allocate certain costs differently in cost accounting (company, division, department, product), it is advisable to discuss the underlying calculation for your own company with the responsible controller who prepares the financial statements.

The operating profit is now also referred to as EBIT (Earnings Before Taxes) in German-speaking countries. The term originates from accounting under IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards). It corresponds to earnings before taking into account interest (both paid and received) and taxes (paid or refunded). Sometimes EBT is reported separately.

The EBIT margin, the ratio of EBIT to sales, serves as an indicator of the "productivity" of a company or product and is also referred to as the profit margin.

EBIT Marge = Ebit/Revenue * 100%

In company publications, EBITA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes and Amortization) is occasionally also reported, which additionally takes into account extraordinary expenses and income as well as company depreciation and amortization (if applicable, "write-ups"). Another term is EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization).

The EBIT margin is an important industry indicator for comparing one's own company with other manufacturers in the same industry. Well-managed and profitable software manufacturers are expected to achieve at least a double-digit EBIT margin, even higher than 20%, while automotive manufacturers have rarely achieved an EBIT margin of more than 7% in recent years. In 2009, the EBIT margin of automotive manufacturers averaged 6.2% worldwide.

In principle, companies that generate an EBIT margin of less than 3% are considered a "dangerous investment".

Industry figures are sometimes published in statistics portals, e.g. statista.com. A list of the EBIT margins of DAX companies can be found here.

When defining and comparing your KPIs, it is essential for product managers to understand which metric their own company refers to as "profit margin". Is it the pure gross margin, the EBT margin or the EBIT margin? Because this (company) profit margin is usually expected from each individual product or product line and therefore also referred to as product margin.

Products are often described as "unprofitable" as soon as they are below the company average, even though they still generate profits. Companies usually dispose of these products or areas first.

For this reason, a product manager should know the product margin well in order to be able to support further investments accordingly. If a product yields a correspondingly high product margin, but does not yet deliver high profits in absolute terms, then, for example, expanding markets, sales, etc. can be a good short-term investment to increase a company's overall profit at the same margin. This is the understanding that management and top management expect from product managers. (see also article: Key Performance Indicators KPIs.

CAPEX and OPEX

CAPEX and OPEX are two further key figures that have become increasingly relevant for companies' cost and budget planning.

CAPEX (CAPital EXpenditure) refers to a company's capital expenditures, which are usually depreciated over longer periods of time, e.g. machines, computer hardware, software licenses.

OPEX (OPerational EXpenditure), is the simplified term for operating costs, i.e. costs incurred in order to maintain the ongoing or operational business of a company. OPEX usually includes costs for the data center, IT operations, operations, sales, marketing, PM and R&D costs.

Understanding the KPIs CAPEX and OPEX is important for product managers, especially with regard to the pricing strategy of end customer prices (see e.g. Open-Product-Management Workflow). This is because in recent years, many companies have seen a shift in available budget pots from CAPEX towards OPEX, especially for investments in the IT area. This has a corresponding effect on the way IT is purchased. For example, in the past, if software was purchased as a license (not leased), and a maintenance and support contract was signed at the same time, the costs for the software licenses were added to the CAPEX costs for accounting purposes, while the costs for maintenance and support were added to the OPEX costs.

Smart sales people, recognizing that their customers did not have enough CAPEX budget available, but still had enough OPEX budget, developed "financing methods" so that purchases could be run through OPEX budget pots, e.g. through appropriate rental or leasing models.

Due to "cloud" pricing models, where costs are usually estimated as a "subscription model" per month, the costs automatically run into the "operating costs" of a company and no longer into the investment costs.

Product managers should be aware of these changes and developments in the purchasing behavior of their end customers in their respective industries in order to set up appropriate pricing models.

The company key figures or financial key figures described in this article are supplemented by sales key figures, market key figures, marketing key figures and product key figures and described in the respective articles.

The question that a product manager should ask himself and must be able to answer at any time is: "What do I answer the managing director, the division manager - generally the top management - when he asks me during the joint ride in the elevator: "How is your product running?".

See the comments on "Elevator Pitch" in the article Key Performance Indicators.

In our experience, PMs very rarely take care of the overall view, sometimes they don't feel responsible at all. In the worst case, the product managers are not even interested in these KPIs.

In the latter case we ask the product managers the question: "How do you want to optimize what you don't know" or "What are your decisions for the next strategic planning based on?".

To be fair, we must say that ignoring KPIs is rarely a holistic phenomenon. Individual KPIs are usually measured, but they are rarely strategically important.

Overview: More articles and information for product managers